Setting the stage for accessible design

Have you ever found yourself scrolling through videos in a location where you couldn’t use audio? You likely used captions to watch the video. This is an example of accessible design benefiting all learners, regardless of their disability status.

In fact, a 2015 Oregon State University Ecampus Research Unit national survey with 3Play Media found that 35% of all course participants used captions often or always, and 54% of participants used captions at least some of the time (Dello Stritto, M.E., & Linder, K). It is incredible to learn that students from the study who did not identify as having a disability used captions almost as frequently as the students who identified as having a disability. It’s clear that even this one element of accessible design has an impact on all students.

There is a common saying among disability advocates, although the initial attribution for the quote is unknown, and it is essentially as follows: “The disability group is one of the only minority groups you can join at any time.” Disability impacts many of us, and the older we live, the more likely we are to find ourselves experiencing a disability. According to the 2019 American Community Survey, 41.1 million or 12.7% of Americans identify as disabled (Census.gov). The United States has legislation that extends to the accessible design of digital content for this very reason.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 paved the way for future legislation by banning employment discrimination based upon race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It also put an end to segregation in public places. Many acts surrounding discrimination recognize The Civil Rights Act as a turning point in US history.

In 1973, the Rehabilitation Act, which includes Section 504 and 508, began and started the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of disability from programs conducted by federal agencies. When people refer to the Rehabilitation Act, they may just refer to it as Section 504. Section 508 is also part of this act and was amended in 1998 through the Workforce Investment Act to include the requirement that federal agencies, and often those organizations receiving federal dollars, make sure their technologies and content are accessible.

The guidelines often followed are the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, or WCAG. The Americans with Disabilities Act (or the ADA) was enacted in 1990. It prohibits discrimination and guarantees people with disabilities have equal opportunities, and was actually modeled after the Civil Rights Act. There are various titles within the ADA that impact state, local, business, and non-profit service providers. Because of these acts, the organization you are employed at or designing content for may fall under these guidelines.

What is accessibility exactly?

According to Iwarsson and Stahl, accessibility can be defined as “an umbrella term for all aspects which influence a person’s ability to function within an environment.” Sometimes it’s easier to take that into the physical space, since that’s where a lot of work in accessibility got its start.

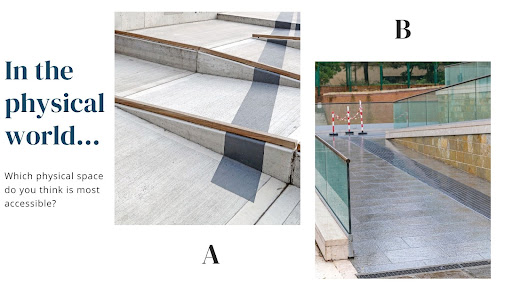

Let’s take a look at these two physical spaces. Which of these two spaces do you think is most accessible? Option A is a small width ramp with multiple turns and small wooden barriers on the side of each drop off. Option B is a large width ramp with two turns and large glass and metal railings to the side of the ramp.

You likely identified that Option B is more accessible. If you consider what it would be like to navigate each of the ramps, you can clearly understand how difficult it would be to navigate a narrow ramp with multiple turns and a very low protective barrier.

Digital accessibility continuously improves, just like our physical designs of ramps. Option A may have been considered a suitable option 30 years ago, but now Option B is more suitable as society has learned more about accessible design. Digital accessibility is the same in this regard – it is always improving, changing, and therefore, what was designed 20 years ago may not meet the accessibility standards of today.

Moodle and accessibility

Moodle is committed to accessibility. It’s designed to provide equal functionality and information to all people. This means there should be no barriers for people regardless of disabilities, assistive technologies that are used, different screen sizes and different input devices. Developers work very hard to ensure accessibility remains top of mind.

As you may already know, we included the Brickfield Accessibility Toolkit beginning in Moodle 3.11+ and we developed a javascript text editor called Atto to specifically focus on accessibility needs. If you are interested in learning more about how to design accessible content with Moodle, we recommend the following resources:

- Accessible Design with the Learner in Mind webinar (6/14/22)

- The ReadSpeaker for Moodle text-to-speech plugin

- Atto Toolbar Accessibility Checker

- Brickfield Accessibility Starter Toolkit

- Lunch and Learn Webinar with Brickfield Labs (November 2021)

- Moodle’s Accessibility Policy

- Several free asynchronous courses on Moodle Academy

From reactive accessibility…

There tends to be two different worldviews in accessible design practices. The first worldview may be something like this:

- “I know accessibility is important, but I’m getting my content from many places, so I just don’t have time.”

- “I just need to get this course out, and I’ll come back to it later.”

- “If someone needs a different format, they’ll ask me and then I’ll deal with it.”

- “The person who made the content is going to be in trouble if it isn’t accessible, not me.”

The examples above reflect more of what we call a reactive mindset toward accessibility, and while it is better to have some commitment to accessibility than no commitment at all, reactive accessibility can set people up for difficulties later. Let’s take the following real life example into consideration:

A university, in their shift to digital delivery models, takes a physical copy of a textbook and copies each page using a standard copy machine (not an Optical Character Recognition or OCR scanner). Each page of the text is now an image, and this is the only copy of the content available to students. Course after course, the instructors follow this same procedure to create digital content. A few years later, a student who uses text-to-speech technology and braille enrolls at the university and discovers content in each course is inaccessible. The student files an official complaint and requests a braille copy of the books. The braille versions of the books take weeks to be delivered, and by this point, the student is so far behind that there is no way the student can catch up. The university ends up with an Office of Civil Rights complaint, and the educational technology department spends months copying textbook pages using the only OCR scanner on campus to fix the problem for future students. The student ends up withdrawing from the university.

In our work as Learning Designers, we have witnessed the pain and difficulty of reactive accessibility. We fully admit that although the stakes may not always be as high as the situation described above, reactive accessibility does happen all the time, and our intent is not to make people feel ashamed for reactively fixing accessibility issues.

Learning about accessibility and taking those lessons forward into the future is what matters. In fact, once an experience like the one described above happens to you, you will likely take those lessons forward and find yourself acting as an accessibility ambassador of sorts within your school or organization.

Therefore, we recommend a proactive accessibility mindset.

…To proactive accessibility

How do you make strides to move toward proactive accessibility? Before getting started, it’s important to gain knowledge about accessible design practices. From there, you can focus on larger organizational changes.

Organization policy

Larger organizational shifts tend to begin with policy. Policies within your organization should support accessibility work. You may be the first person exploring this area within your organization, and that can be a bit intimidating. One thing we’ve heard from many people who are leading these efforts is the importance of sharing conversations to improve buy-in and explain the why behind accessible design.

Once the why is established and buy-in is achieved, work in the policy area of your organization can likely begin. Blending these practices in with policy can help share the load for accessible design as it becomes a collective responsibility, versus the responsibility of the person who interacts most frequently with the site administration settings in Moodle.

Course implementation workflows

From there, we encourage organizations to incorporate accessible design into course implementation workflows. Many organizations follow guidelines to ensure course designs are effective, aligned with objectives, and meeting the needs of all students. Blending accessibility checks in with these guidelines is quite effective. If you are just getting started in the course implementation guideline or workflow area, the SUNY Online Course Quality Review Rubric is a great starting point and they are available through Creative Commons licensing.

Awareness and training campaigns

Once you have developed policy and workflows for course implementation, we recommend you bring the work to a larger audience within your organization. This larger work tends to include accessibility awareness and training campaigns.

One of the most impactful training campaigns we have witnessed included the live demonstration of accessibility by a college student who uses a screen reader each day. The impact he made on the teaching staff was enough to help bring accessible design to the forefront.

During this time, you will likely find other accessibility buddies within your organization who share your passion, and will help to keep an eye on accessible design practices. During the awareness and training campaigns, it’s important to share how to blend accessible design with the work already being created each day. If accessibility is presented as just another checkbox that must be completed or a “have to do,” the mindset tends to be temporary and can lead to issues later.

We also recommend that these training campaigns happen in “bite-sized” chunks, as accessible design can be overwhelming for some and can also be a hard habit to break. Celebrate those small wins and help those who are learning about accessible design to see how far they have come in the process.

Multiple stakeholder reviews

We also recommend that once you start the process of using the guidelines in your day-to-day content design work, you consider adding multiple layers of stakeholder reviews for course design. This stakeholder review process may include having someone unfamiliar with the content but familiar with accessibility look over the course design or it could even include someone who uses assistive technology taking the course for a test drive. This user testing, if possible, can help to also improve guidelines as you see what accessibility concerns are most frequent within your organization. People with multiple accessibility needs are often happy to participate in this process.

Accessibility concern contacts

We also recommend that your organization has an “accessibility concerns” contact. This person may be listed on multiple web pages within your organization as the person to address concerns related to alternative formats for digital content or may be the person to take initial accessibility concerns from the public. By having a person within the organization who is trained to handle accessibility needs of the general public, you are empowering people to self-advocate and get what they want and need from the digital content your organization provides.

Choose content carefully

Finally, we would like to recommend that the content selected for courses is chosen with an accessibility mindset. In the education space in particular, it’s common for educators to use content from many different resources. However, using third party content can be problematic if accessibility is thought of in a retroactive mindset.

We recommend checking documents from third parties for accessibility, which may include downloading the document and using the document editor’s accessibility checker if available. We also recommend asking vendors who may be selling content to educators for a VPAT, or a Voluntary Product Accessibility Template, that explains any accessibility concerns. Most major publishers have VPATs, and many organizations take accessibility to the next level by only approving purchases that have met their VPAT standards.

A more accessible future

These steps can truly help to prevent the reactive accessibility flurry many of us have experienced when designing our courses. With a proactive mindset, you’ll design with all students in mind right from the start.

References

Census.gov. (2021) Anniversary of Americans with Disabilities Act: July 26, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2022 from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2021/disabilities-act.html

Iwarsson, S., & Stahl, A. (2003). Accessibility, usability and universal design – positioning and definition of concepts describing person-environment relationships. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(2), 57-66.

Dello Stritto, M.E., & Linder, K. (2017). A Rising Tide: How Closed Captions Can Benefit All Students. Retrieved June 7, 2022 from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/8/a-rising-tide-how-closed-captions-can-benefit-all-students